IT deduction

Friday, January 27, 2017

"An old soldier, I perceive," said Sherlock.

"And very recently discharged," remarked the brother.

"Served in India, I see."

"And a non-commissioned officer."

"Royal Artillery, I fancy," said Sherlock.

"And a widower."

"But with a child."

"Children, my dear boy, children."

"Come," said I, laughing, "this is a little too much."

Sir Arthur Coonan Doyle. The Greek Interpreter

Nobody is surprised anymore by news reports of fraudsters who’ve called a victim and pretended to work for a bank’s support service, addressing the victim by name, and then lured the victim into forking over a sum of money. Strange but true: If people install an iron door in their house, it is unlikely that they will give the key to a stranger posing as an employee of the company that did the installation. Yet they are quick to divulge their logins and passwords. Why is that? And, by the way, those news reports fail to mention where criminals learn the names of their victims and the size of their bank accounts.

According to research into the Russian database black market, in November 2016 criminals had access to as many as 1.15 billion entries.

Thirty-four percent of those contain data about customers of financial organizations; 19% hold information about shoppers who purchase goods online; 18% of data is obtained from brokers; and 6% of the entries were leaked by telecom operators.

The research also revealed that the databases of 18 large Russian banks were on the black market too.

Database entries contain customers' ID information, their home addresses, account statements, a list of their property as well as data about their taxes and fines. Criminals can use this information to obtain a bank loan in a victim’s name. In some cases, they can blackmail a target and withdraw money from their account. Some databases also include driver license info, bank card and account numbers as well as information about available funds. There are databases related to specific groups of people, e.g., heads of security services, regional directors, retirees, iPhone owners, etc.

Seventy-eight percent of the information is leaked by employees, and over 13% is made available for sale by the very companies that gather it. Another 7% of the data is obtained from public sources. And only 2% is retrieved in hacker attacks.

http://safe.cnews.ru/news/top/2016-12-09_chernyj_rynok_baz_dannyh_v_rossii_otsenivaetsya

Those 7% that have been acquired by collecting data are particularly interesting. Data leaks and hacker attacks occur in the IT environments of companies to which we have entrusted our information (and they are obliged to protect it!), and we can’t make our information any more secure unless we acquire a controlling stake. Collecting information in the World Wide Web is a whole different story.

Naturally, part of the information is indeed extracted from publicly available sources. For example, sites related to conferences and mass media can contain full names and contact information. However, account numbers and available funds aren't normally made available to the general public. But this information can be acquired from infected computers.

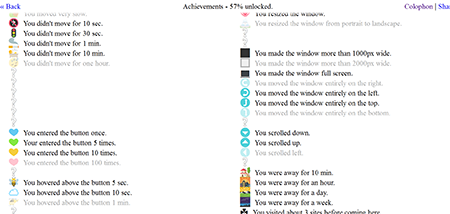

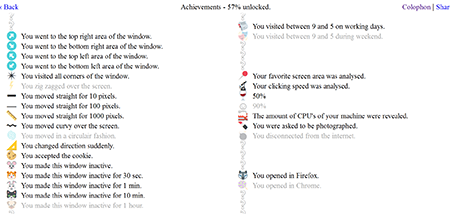

Criminals can get hold of any information that is being entered by a user or is simply stored on a computer. Developers who use debuggers are well aware that in the course of its operation, any program receives a significant amount of data. Those who have nothing to do with software development may find this site particularly interesting: https://clickclickclick.click. A green button against the white background is enough to learn all about what you do on the screen.

Your behaviour, how much time you spend on different activities and even the number of CPU cores in your computer—none of this is a secret. See for yourself!

Of course, this site neither intercepts nor stores passwords and personal information. But other sites (and malware too) aren't so scrupulous, and in our Anti-virus Times issues, we often remind users that all their actions on the Internet are logged somewhere and that true anonymity exists only in dreams and fantasies.

Approximately 8% of all entries contain information that facilitates crimes like forging credit agreements, and committing real estate fraud, bank fraud, and more serious crimes.

http://safe.cnews.ru/news/top/2016-12-09_chernyj_rynok_baz_dannyh_v_rossii_otsenivaetsya

The Anti-virus Times recommends

- The researchers discovered that the information that comes up for sale on the black market is usually about a year old. However, this information typically remains relevant since most users do not change mobile phone numbers or credit cards every year—and they change their passwords even more rarely. We can't prevent leaks of information from organizations that are responsible for the integrity of our data. All we can do is change passwords regularly and refrain from divulging them to a bank’s “support service”.

We can prevent exploits from causing infections by installing updates, but we can't stop sites from tracking our actions.

A simple analysis of data that is available on the Internet can yield somewhat unexpected results. For example, any man who “likes” a MAC cosmetics page is likely to be gay. Conversely, anyone who likes the hip-hop band Wu-Tang Clan from New York is highly likely to be heterosexual. A Lady Gaga fan is probably an extrovert, while people who “like” philosophic posts are introverts.

An analysis of 68 likes on Facebook provides sufficient information to determine the subject’s skin colour (with 95% probability) and their sexuality (88% probability). And even more than that: their intellectual development, religious preference, and preferences with regard to alcohol, tobacco and drugs. The data also helped determine if the person's parents had divorced before that person reached adulthood. The method turned out to be so good that it enabled the researchers to predict how people would answer certain questions. Soon the researchers were able to learn more about someone's personality from 10 likes on Facebook than his colleagues could ever do. After analysing 70 likes they knew that person better than that person’s friends did. After 150 likes they knew that person better than that person’s parents did. After 300 likes they knew more about that person than that person’s partner did. With more data they could learn more about a person than that person knows about him-/herself.

- Try to avoid visiting non-work-related sites from your office machine—after all, there have been cases of corporate machines being compromised via sites used to order food!

![Shared 15 times [Twitter]](http://st.drweb.com/static/new-www/social/no_radius/twitter.png)

Tell us what you think

To leave a comment, you need to log in under your Doctor Web site account. If you don't have an account yet, you can create one.

Comments

Неуёмный Обыватель

05:17:09 2018-08-24

vasvet

08:18:37 2018-07-21